Image via Wikipedia

The Art of Living

Posted By Stewart K Lundy On March 10, 2009 @ 1:21 pm In Philosophers & Saints, Writers & Poets

[1]

[1]

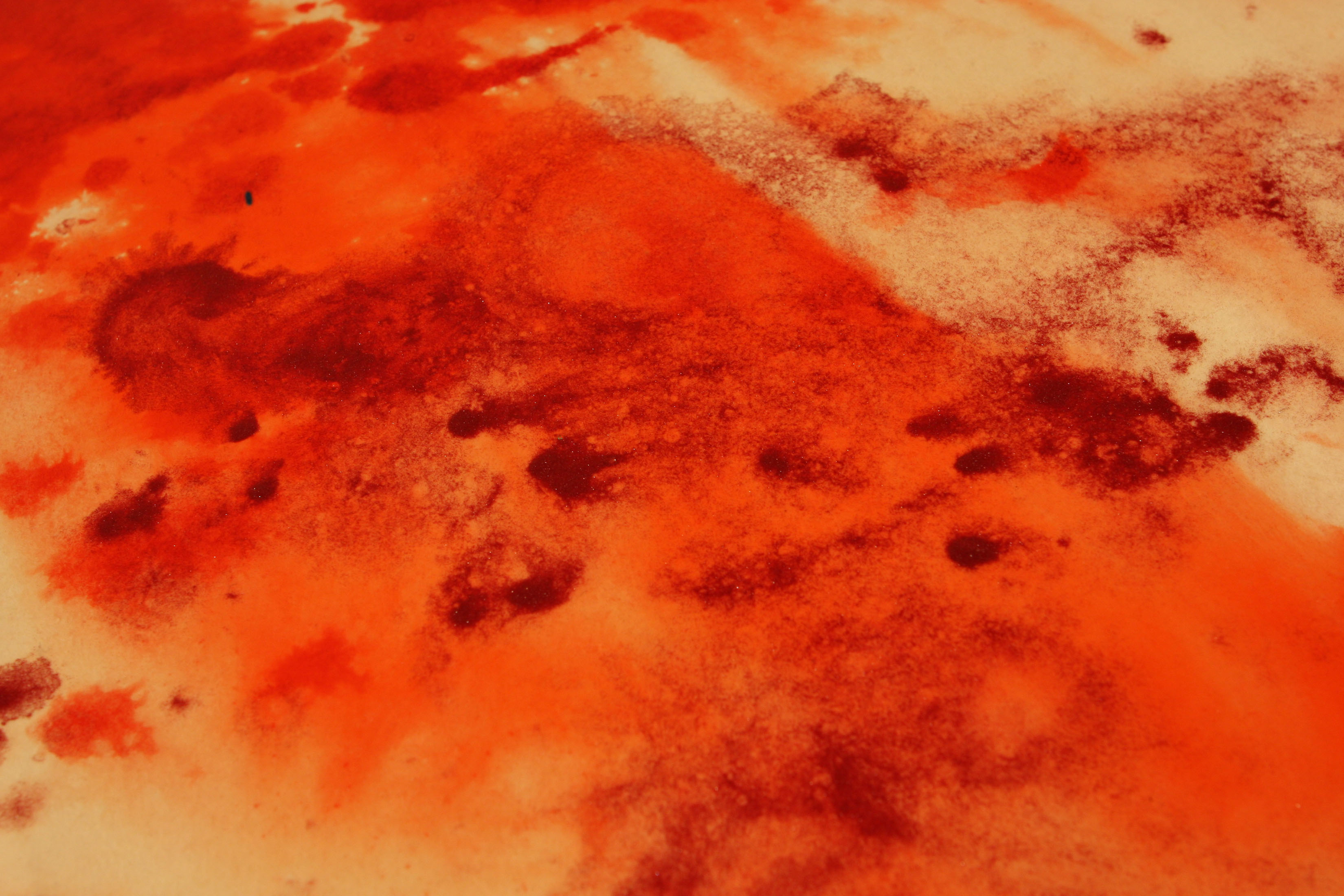

“Little Gidding” by Makoto Fujimura [1], 2007.

Ignorance is the source of knowledge, silence is the source of noise, and stillness is the source of change. The emptiness of the future provides the possibility for movement. This is the principle of conservatism: preserving not only possibility, but the very possibility of possibilities. This impulse is conservative, but never at the expense of future generations. Conservatism is the art of living.

“The best people have a nature like that of water. They’re like mist or dew in the sky, like a stream or a spring on land. Most people hate moist or muddy places, places where water alone dwells. . . . As water empties, it gives life to others. It reflects without being impure, and there is nothing it cannot wash clean. Water can take any shape, and it is never out of touch with the seasons. How could anyone malign something with such qualities as this.”

— Ho-Shang Kung in Red Pine’s translation of the Tao Te Ching [2].

Why the example of water? Water is inherently conservative, conforming to its conditions yet remaining essentially the same. Water prefers stillness. If it is a stream, it runs downhill until it finds a resting place; but it is always in the process of changing, yet it is always only water. In the same way, the essence of conservatism is always the same, even though its conditions constantly change. Were conditions to cease their perpetual flux, conservatism comes to rest as a tranquil pond. The goal of conservatism is tranquility.

In itself, conservatism is tranquil. In relation to the ever-changing human condition, conservatism is always adapting. Conservatism is “formless” like water: it takes the shape of its conditions, but always remains the same. This is why Russell Kirk calls conservatism the “negation of ideology” in The Politics of Prudence [3]. It is precisely the formlessness of conservatism which gives it its vitality. Left alone, the spirit of conservatism is essentially what T.S. Eliot calls the “stillness between two waves of the sea” in “Little Gidding” of his Four Quartets [4]. Conservatism is both like water and the stillness between the waves—the waves are not the water acting, but being acted upon; stillness is the default state of conservatism:

Not known, because not looked for

But heard, half-heard, in the stillness

Between two waves of the sea.

Quick now, here, now, always—

A condition of complete simplicity

Like the Greek concept of kairos—acting in the right way, for the right reasons, at the right moment—this sort of waiting is simply careful conservatism. Conservatism is responsive, reactionary, reserved. Conservatism waits. Perhaps this is why conservatism is most needed in the modern age of mobility. Being careful, and above all patient is crucial to doing something right. Realizing that one does not know the best way of doing anything guarantees not that one will find the best way, but that one might not find the worst way. The same principle applies to knowledge: conservatism (hopefully) does not pretend to know the definitive way, but rather professes the virtue of ignorance with the quiet hope of finding knowledge.

Which is purer? Claiming to know when one does not, or claiming not to know when one does? True knowledge is ignorance—like Socrates’ maxim, “I know nothing except the fact of my ignorance.” To proclaim one’s ignorance sincerely is to remain open to one’s historical, cultural, and cosmological place. Admitting one’s indebtedness requires a healthy dose of humility [5]. As my father says, “Humility is in short supply and has a short shelf life.” To merit anything, we must first exist; therefore, existence is wholly unmerited grace. Accepting the gift of one’s place and giving it to others is humble graciousness. The knowledge we receive is a gift, not something we have merited. The default state of all human beings is ignorance. We are born into the world ignorant and only after that find knowledge. As C.G. Jung observes in Man and His Symbols [6], with the birth of consciousness come the faults of knowledge. It is no coincidence that the Fall came when Adam and Eve ate of the Tree of Knowledge. Was the acquisition of this knowledge itself sin? The first sin was more likely what John Milton says in Book III of Paradise Lost [7]: ingratitude.

Since the aboriginal catastrophe [8], our knowledge has expanded and we have become more conscious of ourselves, for better or worse. The conscious life is definite and directed. Everything of which we are ignorant is indefinite and undirected. But our ignorance is the source of our knowledge. The conscious life remains a static ecstasy [9], a perpetual process always adapting to the environment. If done well, this is the art of life.

According to Okakura Kakuzo’s short work, The Book of Tea [10], this conservative impulse is the “art of being in the world.” Isn’t this “art of life” precisely the virtue Alasdair MacIntyre claims we have lost in his After Virtue [11]? Humility, gratitude [12], and the pursuit of virtue affirm nature as normative not because it dictates morality but because it is a gift. Nature surely does not mean to us what it did to the Scholastics, but I wish we could rediscover the earth as our home. The loss of a normative sense of nature has set up the world against the earth in a destructive manner. We can thank the likes of William of Occam, Francis Bacon, and Descartes for the loss of nature and the birth of modern science. It used to be that nature was seen as the artwork of God, as an acheiropoieta (an icon “not made by human hands”). But no longer do we see nature as an icon, giving glimpses of God; instead, we see nature as blocking us from God. Instead of seeing truth through the physical world, fideism sees truth in spite of the physical world and its natural counterpart, atheism, limits truth to the physical world. Speaking of the spiritual realm as “supernatural” is only a step away from speaking of the “unnatural” realm. The natural-supernatural divide has cut off access to God. The death of God followed the death of nature. Before, creation was seen as the art of God; now, creation is dead and so is its Creator.

Much has been attempted to restore the meaning of creation. Ironically, in a post-mythological era, the religious name “Gaia” has reached the height of its mythological significance. The environmentalism of this epoch is a desperate attempt to recover the lost “art of being in the world.” Some of this comes out in the absurd religious impulses such as neo-paganism which try to recreate the mythical value of the cosmos. I fear none of these attempts to “go back” will succeed. The more technology separates us from nature, the more separated we will feel from God. But we cannot spontaneously return to the “simple life.” In fact, calling any life “simple” means that we no longer live it. In the same way, calling something “unconscious” means that we are no longer unconscious. The simple life will always remain the goal, but attempts to force it destroy simplicity. There is something enviable in those quiet lives which are never trespassed by questions of “place” or “limits” or “liberty.” None of us live simple lives, and certainly none of us who write about simplicity. If someone writes about something, he considers it a problem. Aristotle and Plato wrote about politics not because politics worked, but because politics didn’t work. If something were not first a problem, I doubt whether there would even be a word for it. I write about the “art of life” because it is a problem and because I do not grasp it. The people who best live the “art of life” have probably never heard of it.

Technology and art are at odds like never before. We have lost sight of the truth. Technologically, we are more advanced than we have ever been. But what about artistically? There are few artists today who consider the ontological bearing of art, and even fewer who use art to communicate grace [1]. As tools are necessary for art—brushes, pigments, canvas—so technology is simply a tool for the art of living. Technology is in its essence incomplete [13], waiting to be fulfilled by its use as part of art. Today the technology of living, which focuses on youth, longevity, and pleasure subverts the art of living which focuses on maturity, sustainability, and truth. The art of living has been replaced with the technology of living. I do not know how we can return to the art of living.

Related posts:

- Limbaugh vs. the Front Porch [5] DALLAS, TX. I am bemused, appalled, and fascinated —...

- David Brooks Does (In) Edmund Burke [14] SOUTH BEND, IN. Edmund Burke’s reputation has suffered much...

- Prosperity, Myth and Liberty [15] E.D. Kain identifies a paradox in modern American conservatism...

- The (“Post-”) Modern Cave: An Allegory of the University [16] Mt. Airy, Philadelphia. Imagine human beings brought up from...

- Freedom Among Themselves [17] CHICAGO, ILLINOIS. E.D. Kain had a fine quote from...

Article printed from Front Porch Republic: http://www.frontporchrepublic.com

URL to article: http://www.frontporchrepublic.com/?p=1197

URLs in this post:

[1] Image: http://www.makotofujimura.com/

[2] Tao Te Ching: http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/1562790854?ie=UTF8&tag=borked-20&linkCode=as2&camp=1789&creative=390957&creativeASIN=1562790854

[3] The Politics of Prudence: http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/1932236554?ie=UTF8&tag=borked-20&linkCode=as2&camp=1789&creative=390957&creativeASIN=1932236554

[4] Four Quartets: http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0156332256?ie=UTF8&tag=borked-20&linkCode=as2&camp=1789&creative=390957&creativeASIN=0156332256

[5] humility: http://www.frontporchrepublic.com/?p=781

[6] Man and His Symbols: http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0440351839?ie=UTF8&tag=borked-20&linkCode=as2&camp=1789&creative=390957&creativeASIN=0440351839

[7] Paradise Lost: http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0140424393?ie=UTF8&tag=borked-20&linkCode=as2&camp=1789&creative=390957&creativeASIN=0140424393

[8] aboriginal catastrophe: http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0312253990?ie=UTF8&tag=borked-20&linkCode=as2&camp=1789&creative=390957&creativeASIN=0312253990

[9] static ecstasy: http://www.kritikmagazine.com/college/getting-from-a-to-b

[10] The Book of Tea: http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/1604596430?ie=UTF8&tag=borked-20&linkCode=as2&camp=1789&creative=390957&creativeASIN=1604596430

[11] After Virtue: http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0268035040?ie=UTF8&tag=borked-20&linkCode=as2&camp=1789&creative=390957&creativeASIN=0268035040

[12] gratitude: http://www.frontporchrepublic.com/?p=1118

[13] incomplete: http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0061319694?ie=UTF8&tag=borked-20&linkCode=as2&camp=1789&creative=390957&creativeASIN=0061319694

[14] David Brooks Does (In) Edmund Burke: http://www.frontporchrepublic.com/?p=985

[15] Prosperity, Myth and Liberty: http://www.frontporchrepublic.com/?p=1031

[16] The (“Post-”) Modern Cave: An Allegory of the University: http://www.frontporchrepublic.com/?p=1717

[17] Freedom Among Themselves: http://www.frontporchrepublic.com/?p=758

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=79392b9e-af18-4633-ad95-f6ae6192eb1d)