Is This the Big One? The Flood That Makes New Orleans A Backwater?

From Down With Tyranny

-by Doug Kahn

In 1882 came the most destructive flood of the nineteenth century. After breaking the levees in two hundred and eighty-four crevasses, the water spread out as much as seventy miles. In the fertile lands on the two sides of Old River, plantations were deeply submerged, and livestock survived in flatboats. A floating journalist who reported these scenes in the March 29th New Orleans Times-Democrat said, “The current running down the Atchafalaya was very swift, the Mississippi showing a predilection in that direction, which needs only to be seen to enforce the opinion of that river’s desperate endeavors to find a short way to the Gulf.”

John McPhee

Atchafalaya

The New Yorker, 2/23/87

The massive surge of water currently moving down the Mississippi River towards the Louisiana Delta may be remembered as the flood that affected New Orleans even more than Hurricane Katrina did. If this is the ‘five-hundred-year flood,’ the one that some say has been looming since 1973, the one that finally overwhelms the Old River Control Structure 300 miles upstream from the current outlet of the Mississippi to the Gulf of Mexico, then New Orleans will be devastated again. By lack of water.

The Mississippi River has been trying to go down the Atchafalaya River to the Gulf of Mexico for hundreds of years now, and we’ve been trying to stop it. Our defenses are going to be tested next week. I just hope the Army Corps of Engineers opens the Morganza Spillway first, prompting the evacuation of everyone in the Morganza Floodway. It’s going to take the cooperation of Louisiana Governor Bobby Jindal. Keep your fingers crossed.

Dr. Jeff Masters is the co-founder of Weather Underground, an invaluable weather site:

The levees on the Lower Mississippi River are meant to withstand a “Project Flood”-- the type of flood the Army Corps of Engineers believes is the maximum flood that could occur on the river, equivalent to a 1-in-500 year flood. The Project Flood was conceived in the wake of the greatest natural disaster in American history, the great 1927 Mississippi River flood. Since the great 1927 flood, there has never been a Project Flood on the Lower Mississippi, downstream from the confluence with the Ohio River (there was a 500-year flood on the Upper Mississippi in 1993, though.) On Sunday [May 1st], Major General Michael Walsh of the Army Corps of Engineers, President of the Mississippi Valley Commission, the organization entrusted to make flood control decisions on the Mississippi, stated: “The Project Flood is upon us. This is the flood that engineers envisioned following the 1927 flood. It is testing the system like never before.”

Alluvial rivers change their courses

John McPhee:

The Mississippi River, with its sand and silt, has created most of Louisiana, and it could not have done so by remaining in one channel. If it had, southern Louisiana would be a long narrow peninsula reaching into the Gulf of Mexico. Southern Louisiana exists in its present form because the Mississippi River has jumped here and there within an arc about two hundred miles wide, like a pianist playing with one hand-- frequently and radically changing course, surging over the left or the right bank to go off in utterly new directions.

Always it is the river’s purpose to get to the Gulf by the shortest and steepest gradient. As the mouth advances southward and the river lengthens, the gradient declines, the current slows, and sediment builds up the bed. Eventually, it builds up so much that the river spills to one side. Major shifts of that nature have tended to occur roughly once a millennium.

The Mississippi’s main channel of three thousand years ago is now the quiet water of Bayou Teche, which mimics the shape of the Mississippi. Along Bayou Teche, on the high ground of ancient natural levees, are Jeanerette, Breaux Bridge, Broussard, Olivier--arcuate strings of Cajun towns.

Eight hundred years before the birth of Christ, the channel was captured from the east. It shifted abruptly and flowed in that direction for about a thousand years.

In the second century a.d., it was captured again, and taken south, by the now unprepossessing Bayou Lafourche, which, by the year 1000, was losing its hegemony to the river’s present course, through the region that would be known as Plaquemines.

By the nineteen-fifties, the Mississippi River had advanced so far past New Orleans and out into the Gulf that it was about to shift again, and its offspring Atchafalaya was ready to receive it. By the route of the Atchafalaya, the distance across the delta plain was a hundred and forty-five miles-- well under half the length of the route of the master stream.

The story will have started upstream. Billions of tons of water, the spring melt from last winter’s snows, added to the rain that the land of over one-third of the continental United States can’t sop up, is spilling down the watercourses that funnel into the Mississippi River. Every spring the rivers rise, the levees hold the rivers back (usually), the tributaries join and then empty their water into Big River. One of them, the Ohio River, comes in at Cairo, Illinois, where the levee is 63 feet high. The water had been expected to crest at 61.5 feet on Tuesday, and stay that high for days. No one knows if the levee can withstand the pressure for that long; the old record high water was 60.5 feet.

You may have read that the Army Corps of Engineers was poised to dynamite the Birds Point Levee just downstream from Cairo, diverting 550,000 cubic feet of water per second onto 133,000 acres of Missouri farmland. That’s supposed to work like a Roto-Rooter visit, draining water away from Cairo, and was designed to lower the river there by 7 feet.

But it may not help people in Louisiana, because the floodway is designed to drain most of that water back into the Mississippi further downstream, at New Madrid. It’ll change the shape of the pulse of water headed south, will certainly add an unknown but tremendous amount of soil; but a lot more can happen before it gets to Red River Landing in Louisiana and tries to take a right turn, drop 20 feet, and slam down the Atchafalaya River. It takes 2 weeks for any one sip of fresh water to make it from Cairo, Illinois to New Orleans and out into the bayous and the Gulf of Mexico.

And rain, a lot of rain, is in the forecast for the next two weeks.

Is the System Working?

The Corps of Engineers dynamited the Birds Point Levee Monday night. Here's the frame by frame video of the breach explosions. At that time the Corps said they hoped to lower the water at Cairo by 4 feet, not the designed 7 feet. The National Weather Service graph at the Cairo river gauge says different:

The river receded not 7 feet or 4 feet but 2 feet. And the rains continue, so we’ll see. In western Tennessee, the tributaries keep rising at Memphis and upstream:

...[Q]uestions remain about whether breaking open the levee would provide the relief needed, and how much water the blast would divert from the Mississippi River as more rain was forecast to fall on the region Tuesday. The seemingly endless rain has overwhelmed rivers and strained levees, including the one protecting Cairo, at the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers.

Flooding concerns also were widespread Monday in western Tennessee, where tributaries were backed up due to heavy rains and the bulging Mississippi River. Streets in suburban Memphis were blocked, and some 175 people filled a church gymnasium to brace for potential record flooding. The break at Birds Point was expected to do little to ease the flood dangers there, Tennessee officials said.

The System that ‘Controls’ the Mississippi

The floods of 1927 might be said to be the cause of the disaster that may happen in 2011, because it was that natural event that resulted in the decision of the Army Corps of Engineers to tame the Mississippi River once and for all. Up to that year, the Corps had been focused on building levees, cutting off loops in the river, dredging channels. Reducing sedimentation had been thought key to maintaining the river’s depth, improving navigation, and making high-water pulses flow downstream as quickly as possible.

McPhee:

The ’27 high water tore the valley apart. On both sides of the river, levees crevassed from Cairo to the Gulf, and in the same thousand miles the flood destroyed every bridge. It killed hundreds of people, thousands of animals. Overbank, it covered twenty-six thousand square miles. It stayed on the land as much as three months. New Orleans was saved by blowing up a levee downstream. Yet the total volume of the 1927 high water was nowhere near a record. It was not a hundred-year flood. It was a form of explosion, achieved by the confining levees.

The plan changed. Here’s how the Corps now summarizes its mission on the Mississippi:

The Mississippi River & Tributaries (MR&T) project was authorized by the 1928 Flood Control Act. ... Administered by the Mississippi River Commission under the supervision of the Office of the Chief of Engineers, the resultant MR&T project employs a variety of engineering techniques, including an extensive levee system to prevent disastrous overflows on developed alluvial lands; floodways to safely divert excess flows past critical reaches to ease stress on the levee system [my emphasis]; channel improvements and stabilization features to protect the integrity of flood control measures and to ensure proper alignment and depth of the navigation channel; and tributary basin improvements, to include levees, headwater reservoirs, and pumping stations, that maximize the benefits realized on the main stem by expanding flood protection coverage and improving drainage into adjacent areas within the alluvial valley.

The Corps is responsible for the design, construction, and operation of a 485-mile-long Rube Goldberg contraption which both prevents and causes disastrous flooding. The Birds Point–New Madrid Floodway and four other downstream floodways are parts of the mechanism. Others include the levees that overtopped when the Gulf of Mexico surged up into New Orleans during Hurrican Katrina. The most ambitious (and perhaps hubristic) part of the system is at the Old River Control Structure. That’s a spillway built where the Red River used to used to flow out of Texas via Arkansas and pour its contents into the top of a looping bend the Mississippi made to the west. That was before the Atchafalaya, which flowed out of the bottom of the loop, snatched it in the 1940s.

Here’s the Plumbing

Controlling the river is a grand concept. Mississippi floods are disasters that, if they don’t carry off the people themselves, carry off all their worldly possessions, destroy their farms and the businesses they work for. The Corps realized after 1927 that sometimes the river was just too high for levees to contain, and the floodways were built, relief valves that could spread the water out. (They didn’t buy up the land in the Birds Point-New Madrid floodway, they used eminent domain to create “flowage rights”, and with a one-time payment bought the right to flow water over it when necessary. This week that happened for only the second time.) The downstream end of the floodway system is the Bonnet Carré Spillway in St. Charles Parish, whose 350 bays can (and pretty soon will) be opened to divert 250,000 cubic feet per second into Lake Ponchartrain, keeping the Mississippi River 3 feet below the top of 20-foot-high New Orleans levees.

The Bonnet Carré Spillway

The challenge evolves, because the river keeps changing

It had become more obvious that each year, accelerating in the 1940s, increasing flow was going down the Atchafalaya. In 1850 10% of the Red and Mississippi flow emptied down the Atchafalaya. In 1900 it was 13%, 18% in 1920, 23% in 1940, and 30% by 1950. In 1951 came the study with a firm prediction that at some point in the decade after 1965, once 40% was going down the Atchafalaya, the process would be irreversible, and the Mississippi would shrivel.

So the masters of creation from Pacific to Atlantic (the U.S. Congress) in 1954 decreed that “the distribution of flow and sediment in the Mississippi and Atchafalaya Rivers is now in desirable proportions and should be so maintained.” That is, that 70% of the water should continue down the Mississipi to New Orleans, and 30% should run down to Morgan City in the Atchafalaya. In major flood years, that dictates that the Old River defenses of the Army Corps of Engineers should master 2 million cubic feet of water, or 65,000 tons, every second. 5,616,000,000 tons a day. The Old River Control Structure, completed in 1963, was designed to be that defense.

So the masters of creation from Pacific to Atlantic (the U.S. Congress) in 1954 decreed that “the distribution of flow and sediment in the Mississippi and Atchafalaya Rivers is now in desirable proportions and should be so maintained.” That is, that 70% of the water should continue down the Mississipi to New Orleans, and 30% should run down to Morgan City in the Atchafalaya. In major flood years, that dictates that the Old River defenses of the Army Corps of Engineers should master 2 million cubic feet of water, or 65,000 tons, every second. 5,616,000,000 tons a day. The Old River Control Structure, completed in 1963, was designed to be that defense.If you read further down, you’ll see that a flood in 1973 proved the Corps’ design to be fallible. They subsequently added the Auxiliary Control Structure, another spillway, so now the system will definitely, definitely work as advertised. But short of testing the system by flooding everyone on the route down to Morgan City and drying up the Mississippi down the other way, how do you answer this question: can you really control the river?

Add a total unknown: what’s to stop the Mississippi from breaking through the levees close upstream, heading west from there, flanking the Maginot Line?

McPhee:

I once asked Fred Smith, a geologist who works for the Corps at New Orleans District Headquarters, if he thought Old River Control would eventually be overwhelmed. He said, “Capture doesn’t have to happen at the control structures. It could happen somewhere else. The river is close to it a little to the north. That whole area is suspect. The Mississippi wants to go west. 1973 was a forty-year flood. The big one lies out there somewhere—when the structures can’t release all the floodwaters and the levee is going to have to give way. That is when the river’s going to jump its banks and try to break through.”

Water goes where it wants to go. Both the Red River and the Mississippi River used to run south at this spot, pretty much parallel to each other. As always happens in the Mississippi, the riverbed silted up and water was diverted further and further to the west, resulting in what became known as Turnbull’s Loop:

By 1500 the loop had changed, and then by 1831 had invaded the Red River.

By then the Army Engineers had hired a civilian named Henry Shreve (Shreveport, yes) as ‘Superintendent of Western River Improvements’. Anyone who has read Samuel Clemens’ descriptions of Mississippi River life remembers the danger posed by ‘snags’, dead trees that lie just under the surface, waiting to rip a steamboat hull. Shreve fitted out a steamboat to drag snags out of the rivers. He irreversibly changed the Mississippi, first by clearing a 160-mile-long dead tree jam on the Red River that had blocked flow down the Atchafalaya.

Shreve creates the Old River by cutting the loop

McPhee:

In the sinusoidal path of the river, any meander tended to grow until its loop was so large it would cut itself off. At 31 degrees north latitude was a westbending loop that was eighteen miles around and had so nearly doubled back upon itself that Shreve decided to help it out. He adapted one of his snag boats as a dredge, and after two weeks of digging across the narrow neck he had a good swift current flowing. The Mississippi quickly took over. The width of Shreve’s new channel doubled in two days. A few days more and it had become the main channel of the river.

The great loop at 31 degrees north happened to he where the Red-Atchafalaya conjoined the Mississippi, like a pair of parentheses back to back. Steamboats had had difficulty there in the colliding waters. Shreve’s purpose in cutting off the loop was to give the boats a smoother shorter way to go, and, as an incidental, to speed up the Mississippi, lowering, however slightly, its crests in flood. One effect of the cutoff was to increase the flow of water out of the Mississippi and into the Atchafalaya, advancing the date of ultimate capture. Where the flow departed from the Mississippi now, it followed an arm of the cutoff meander. This short body of water soon became known as Old River. In less than a fortnight, it had been removed as a segment of the main-stem Mississippi and restyled as a form of surgical drain.

The ‘Old River’ in 1839

The Old River Control Structure

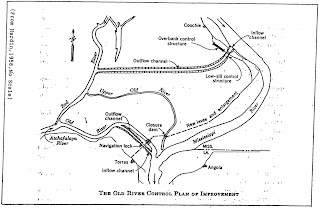

In the above diagram, the ‘Upper Old River’ and ‘Old River’ are what’s left of Turnbull’s Loop. The ‘Navigation Lock’ at the bottom allows ships to go from one river to the other. Levees keep guard on the Mississippi, should it ever get the idea of charging west. The Old River Control Structure is here called the ‘Low-sill control structure’. All of these structures are built on dried out mud. The closest bedrock is 7,000 feet down.

The 1973 flood

The Tennessee and Missouri Rivers supplied the water. McPhee:

The Corps had built Old River Control to control just about as much as was passing through it. In mid-March, when the volume began to approach that amount, curiosity got the best of Raphael G. Kazmann, author of a book called “Modern Hydrology” and professor of civil engineering at Louisiana State University. Kazmann got into his car, crossed the Mississippi on the high bridge at Baton Rouge, and made his way north to Old River. He parked, got out, and began to walk the structure.

“That whole miserable structure was vibrating,” he recalled in 1986, adding that he had felt as if he were standing on a platform at a small rural train station when “a fully loaded freight goes through.” Kazmann opted not to wait for the caboose. “I thought, This thing weighs two hundred thousand tons. When two hundred thousand tons vibrates like this, this is no place for R. G. Kazmann. I got into my car, turned around, and got the hell out of there. I was just a professor-- and, thank God, not responsible.”

Kazmann says that the Tennessee River and the Missouri River were “the two main culprits” in the 1973 flood. In one high water and another, the big contributors vary around the watershed. An ultimate deluge might possibly involve them all.

The precipitation that produced the great flood of 1973 was only about twenty per cent above normal. Yet the crest at St. Louis was the highest ever recorded there. The flood proved that control of the Mississippi was as much a hope for the future as control of the Mississippi had ever been. The 1973 high water did not come close to being a Project Flood. It merely came close to wiping out the project.

The Structure is repaired-- Kind of

In the words of the Corps, “The partial foundation undermining which occurred in 1973 inflicted permanent damage to the foundation of the low sill control structure. Emergency foundation repair, in the form of rock riprap and cement grout, was performed to safeguard the structure from a potential total failure. The foundation under approximately fifty per cent of the structure was drastically and irrevocably changed.”

Robert Fairless, a New Orleans District engineer who has long been a part of the Old River story, once told me that “things were touch and go for some months in 1973” and the situation was precarious still. “At a head greater than twenty-two feet, there’s danger of losing the whole thing,” he said. “If loose barges were to be pulled into the front of the structure where they would block the flow, the head would build up, and there’d be nothing we could do about it.”

The Auxiliary Control Structure

(Another Spillway. Genius.)

The Corps took pressure off the damaged Structure by building an additional spillway downstream, and a hydroelectric dam immediately upstream:

The Corps pegs the “Project Flood” at Red River Landing at 3,000,000 cubic feet per second. If you prevent the Mississippi from flowing down the Atchafalaya, then New Orleans ends up underwater. The plan is that half of the 3,000,000 cfs could be diverted down the Atchafalaya, some of that when it reaches another relief valve, the Morganza Spillway just south of the Old River complex. The Corps will open this up when the flow reaches 1,500,000 cubic feet per second, estimated to be next Wednesday, May 12.

So will this flood reach the levels of 1973? Vicksburg is just 120 miles upstream, and this forecast from the National Weather Service calls for a crest on June 18th higher than the 1973 flood, the one that shook the Old River Control Structure, which is now almost 40 years older.

945 PM CDT FRI APR 29 2011

THE FLOOD WARNING CONTINUES FOR

THE MISSISSIPPI RIVER AT VICKSBURG

* UNTIL FURTHER NOTICE.

* AT 9:00 PM FRIDAY THE STAGE WAS 42.8 FEET.

* MAJOR FLOODING IS FORECAST.

* FLOOD STAGE IS 43.0 FEET.

* FORECAST...THE RIVER WILL RISE ABOVE FLOOD STAGE BY TONIGHT AND

WILL CONTINUE TO RISE TO NEAR 53.5 FEET BY WEDNESDAY MORNING may 18th.

this crest is higher than the flood of 2008 by 2.5 feet and

the flood of 1973 by 0.3 feet.

Defenses against the river’s assault have been strengthened since 1973, so things might be okay, so long as it stops raining. The predictions don’t include rain that hasn’t fallen yet. The latest projection for Vicksburg river levels:

Yes. Now the prediction calls for a level equalling 1973 not on May 18th, but by May 9th.

Why is this happening now?

It’s getting harder to deny that something is changing the weather. November 2010 was the warmest ever recorded. Camarillo, California heated up to 83º last Sunday, a record. Lancaster, 85 miles away, registered a record cold of 32º. The residents of Alabama and other states last week suffered the devastation of the 3rd largest tornado outbreak ever recorded. The outbreak of April 14–16 is now only the 4th largest.

From Jeff Masters’ blog post of April 27:

Sea surface temperatures (SSTs) in the Gulf of Mexico are currently close to 1°C above average. Only two Aprils since the 1800s (2002 and 1991) have had April SSTs more than 1°C above average, so current SSTs are among the highest on record. These warm ocean temperatures helped set record high air temperatures in many locations in Texas yesterday, including Galveston (84°F, a tie with 1898), Del Rio (104°F, old record 103° in 1984), San Angelo (97°F, old record 96° in 1994). Record highs were also set on Monday in Baton Rouge and Shreveport in Louisiana, and in Austin, Mineral Wells, and Cotulla la Salle in Texas. Since this week’s storm brought plenty of cloud cover that kept temperatures from setting record highs in many locations, a more telling statistic of how warm this air mass was is the huge number of record high minimum temperature records that were set over the past two days. For example, the minimum temperature reached only 79°F in Brownsville, TX Monday morning, beating the previous record high minimum of 77°F set in 2006. In Texas, Austin, Houston, Port Arthur, Cotulla la Salle, Victoria, College Station, Victoria, Corpus Christi, McAllen, and Brownsville all set record high minimums on Monday, as did New Orleans, Lafayette, Monroe, Shreveport, and Alexandria in Louisiana, as well as Jackson and Tupelo in Mississippi. Since record amounts of water vapor can evaporate into air heated to record warm levels, it is not a surprise that incredible rains and unprecedented floods are resulting from this month’s near-record warm SSTs in the Gulf of Mexico. [My emphasis.]

Super-cell thunderstorms and the tornados that accompany them develop when a cold front sweeps through areas where the air is hot and very humid. And right now humidity is billowing up through tornado alley from the Gulf of Mexico. The 1ºC Dr. Masters was talking about may not sound like much, but a cubic foot of water stores vastly more energy than the same volume of air does; the intensity of a hurricane can be predicted by the ‘heat content’ of the top layer of water (up to 500 feet deep) that it’s passing over.

The Loop Current is an ocean current that transports warm Caribbean water through the Yucatan Channel between Cuba and Mexico. During summer and fall, the Loop Current provides a deep (80–150 meter) layer of vary warm water that can provide a huge energy source for any lucky hurricanes that might cross over.

The Loop Current commonly bulges out in the northern Gulf of Mexico and sometimes will shed a clockwise rotating ring of warm water that separates from the main current. This ring of warm water slowly drifts west-southwestward towards Texas or Mexico at about 3-5 km per day. This occurred in 2005, when a Loop Current Eddy separated in July, just before Hurricane Katrina passed over and “bombed” into a Category 5 hurricane. The eddy remained in the Gulf and slowly drifted westward during September. Hurricane Rita passed over the same Loop Current Eddy three weeks after Katrina, and also explosively deepened to a Category 5 storm.

This animation of warm water currents in the western hemisphere explains a lot; why New Orleans is a dangerous place to live, why the Mississippi is the 5th largest river in the world (by volume of water), and why the southern portion of Louisiana even exists in the first place. Water boils up from the Gulf and fills the low pressure systems moving eastward across the United States, gets dumped (with the airborne dirt that raindrops form around) on the 1,245,000 square miles of the watershed that feeds (among many others) the Big Black, Red, White, Arkansas, Ohio, Illinois, Tennessee, Missouri, and Mississippi rivers, scours the surface of the earth in 31 states and rushes sediment back down to the Gulf at Mud Bay, near Burrwood Bayou. Before 1900, before we ‘controlled’ the Mississippi, 400 million metric tons of sediment was added to the State of Louisiana every year.

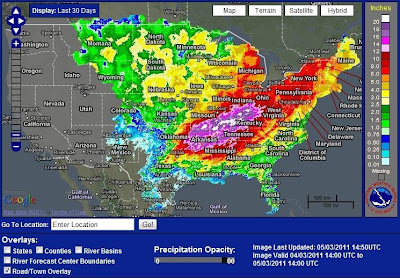

Here’s 30 days worth of rainwater on its way to Louisiana:

Labels: climate change, Mississippi River